Tjen Folket Media. Originally published in Norwegian on the 27th of March, 2020.

This article will be trying to give a small insight into an important event in the Korean communist movement’s history and the line struggle that took place. This is not a complete overview, and the article may contain some shortcomings.

This article will also not provide any comprehensive political-ideological critique of the rightist line in the Workers’ Party of Korea. The Korean communist movements history is something that should be studied more thoroughly, and hopefully can this text serve as a starting point for further discussion.

It is three years since the Korean war and the contradictions in the ‘’Workers’ Party of Korea’’ reached the boiling point. On the second plenary in the party’s third central committee the struggle between the left and right line in the party reaches a climax. This culmination of the struggle between left and right is known as the ‘’August Incident’’ and came to have catastrophic consequences for the left line in the party.

The Context

Korea got occupied by the expanding Japanese empire in 1910. The occupiers violently subdued the Korean people, and the police and military carried out bloody massacres. After nine years of occupation, a fierce freedom movement took place, called the March 1st Movement.

But the movement was brutally suppressed by the Japanese occupiers, and many of the people who participated in the movement were forced into exile, to places like China. Among these we have multiple key people who were going to become important for the left line in the Workers’ Party of Korea, for the next twenty-five years.

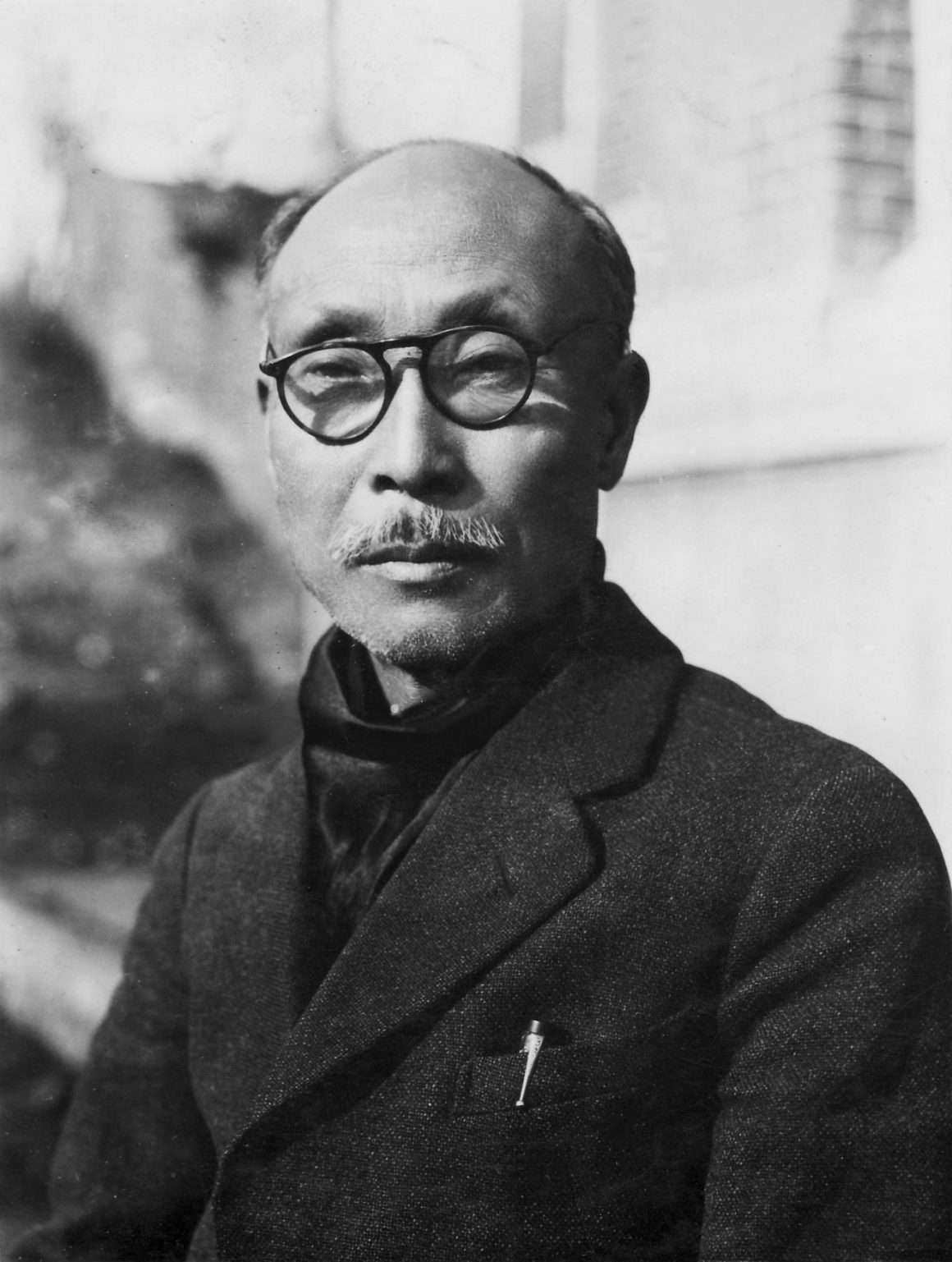

It was around this time that the Communist Party of China (CPC) was founded, and as the communist movement grew, the exiled Koreans also joined the party. One of them was Mu Chŏng.

He started as a Soldier in the Eighth Route Army in the Chinese liberation war against Japan. He excelled both militarily and politically, this led to him gaining prominence in the party. Eventually he became the supreme commander of the Korean Volunteer Army, who took part in the Chinese people’s war against Japan and the Kuomintang. The party looked at Mu Chŏng as a potential future leader for the communist movement.1

Gradually both the Koreans and the exile-Koreans began to constitute organizations for resistance against the Japanese occupation of Korea. Several of these were active in guerrilla combat against the occupation, and some got direct help from the Chinese communists.

The Soviet Union liberated the northern part of Korea during world war 2, while the US occupied the southern part. Negotiations to unite Korea failed, and the country got cut in half. The socialist northern part ruled by the newly formed unity party the ‘’ Workers’ Party of Korea’’ with Kim Tu-Bong as chairman. And the capitalist southern part ruled by the USA-puppet Syngman Rhee.

The Soviet Red Army withdrew from Korea in 1948. The same did most of the American troops the year after. But the sparks between the north and south soon caught fire, and on June 25, 1950, there was once again war. With the Soviet Union and China supporting the people’s republic in the north, and USA, UN and several others supporting the south.

Kim Il-Sung got elected chairman instead of Kim Tu-bong a year before the Korean-War. Kim Il-sung was the leader of the right opportunist line in the party. Already during the war did they begin to consolidate their power, and Kim Il-sung lead a purge against the red line, which he saw as a threat. He focused on removing the representatives for the left line that held important positions in the army.

Mu Chŏng was one of the foremost leaders of the left line and was one of the first to get purged. He lost his role as second in command of the army already in December 1950,2 and he died only two years later. The red line, which was initially very dominant in the army, had a minority left with important positions when the war was over. Something that would have fatal consequences.

The Breaking Point

The year is 1956. The year of counter-revolution. The capitalist roaders coup the Soviet Union and the Eastern European states. In February, Nikita Khrushchev is holding his ‘’secret speech’’ where he breaks with Stalin and with Marxism-Leninism. The left line in the party (Bolsheviks) is systematically purged, jailed and killed. It was in the cards that the right line in the Worker’s Part of Korea to try something similar.

The party arranges its third congress in April, and here the contradictions between the left and right line starts to manifest. But attempts to address criticism are actively sabotaged. The submitted text that are to be the starting point of discussion, is ruthlessly edited by the meeting management, 3 which was dominated by the right opportunist line.

Kim Il-sung travels with a state delegation to visit the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe only four months after Khrushchev’s ‘’secret speech’’. There they meet with Khrushchev. At the same time the left line in the homeland begins to prepare to handle the right line in their own party, the one lead by Kim Il-sung.

Defence minister Choi Yong-kun, a devoted proponent of the right line, finds out what the left line is preparing to do. He sends a telegram to Kim Il-sung where he depicts the activity of the left line.4 In response Kim Il-sung implemented drastic measures.

The party’s general meeting was postponed from August 2 to August 30, and the assembly was notified only one day in advance. Kim Il-sung in secret ordered the army to stationed combat troops along the border.5 Soldiers in civilian clothing were sent to all parts of the capital Pyongyang.6 In addition, two army divisions were deployed north of the city.

The whole thing was an opportunistic and cunning stunt to confuse and intimidate the left of the party, in an attempt to put them out of play. As a result, the mood in that plenary, but also in Pyongyang in general was down. But the red line refused to back down.

Kim Il-sung opened the assembly with a report on the state delegation’s trip to the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, but abruptly changed the theme at the end of his report.

The ending words was a clear warning to what was in store for the opposition. If you brought up criticism, you would be considered an enemy of the party.

[…]enemies are thinking of splitting our Party with this and trying to provoke conflict in relations between us and the fraternal countries. Therefore it is necessary to increase vigilance.7

Kim Il-sung, the inaugural speech of the Third Central Committee’s second plenary, August 1956

The next speech was by Yun Gong-heum, a part of the left line. The representatives for the right line tried to cut off his speech by shouting and screaming.8

But he tried to continue his speech nevertheless. Over the shouts one could initial hear fragments:

Methods of threats and surveillance are being employed with regard to our comrades, who are devoted to the Party and the revolution and who offered constructive opinions and suggestions, […] He himself* grossly tramples on intra-Party democracy and suppresses criticism; these actions completely contradict the Party charter and the Leninist norms of Party life; this means undermining revolutionary Marxist-Leninist principles.9

As a result of the right line’s active sabotage the atmosphere in the hall became chaotic. Kim Il-sung and the meeting management did nothing to intervene and put an end to the unrest. On the contrary they called for it, by joining in on the shouting. It was obvious that they had planned and practiced this before.

The speech was eventually completely drowned out in the shouting. Then Kim Il-sung proposed that ‘’reactionaries who are against the party’’ should not have to option to hold a speech, and that the debate should end.

Choe Chang-ik, was one of the leaders from the left line him and others proposed that the discussion should continue. But they were also scolded and harassed. The chair of the meeting paid no attention to this proposal and went on to vote on Kim Il-sung’s proposal. The vote ended with a majority in favour of ending the debate.

During the afternoon plenary it was Choe Chang-ik’s turn to hold his speech. Marked by the events of the morning plenary, he was unable to get his message across. Once again the troublemakers began to shout and yell.

The Consequences

Kim Il-sung put forward the next day a proposal to exclude more of the left line from the central committee, including Choe Chan-ik.10

Then he proposed to exclude more of them from the party. A majority voted in favour and both proposals were thus adopted. In addition to the right line, some centrist also voted in favour, fearing they would be next.

Choe Chang-ik in a conversation with a Soviet diplomat a month later explains one of the problems with the party. The incorrect way the party leadership chose party members for office. Instead of choosing people using Marxist-Leninist principles and by their abilities, they are chosen based on their loyalty to the right line.11

This may explain why a majority voted in favour of Kim Il-sung’s proposals, even though the left line was the majority of the party.12

With that the meeting was done for the day. When they returned home people in the left line found their phone lines cuts.13

It occurred to them that they were likely to be arrested during the evening. Four of them escaped to China during the night, and sent a letter about the crisis in the part to the politburo in the central committee to of the CCP. In the letter, they write in addition to a criticism of the Korean leadership, among other things, about the reason why they fled to China:

We think that if Kim Il Sung had arrested and executed us this would not have brought the revolution any good.14

The right line started in December a five-month-long purge campaign, where around 300 members who were part of the left line got excluded from the party.15

As the left line had lost much of its influence on the party, there were only a few generals left, who were purged at the end of ’56.

This aroused reactions from both China and the Soviet Union. Mao met with a delegation from the Worker’s Party of Korea, where he criticized them on the handling of what was going to be known as the ‘’August incident’’. He urged them to establish a dialogue with comrades with differing opinions through factual discussions in a general meeting, and release the arrested comrades, as well as give them back their positions in the party.

Both the Chinese and Soviet diplomats urged Kim Il-sung not to carry out the execution of among others, Pak Hon-yong, one of the excluded members. Kim Il-sung agreed to the points raised by the party delegation. But nothing changed, and Pak Hon-yong was executed.

In January 1957 during the general assembly, Kim Tu-bong was yet again criticised and stripped of his duties. A year later he disappeared. He was probably executed or shot trying to escape to China. Choe Chan-ik, and several others from the left line were also abducted and executed.16

In the summer, the same year even more party members were arrested when they tried to escape to China. Another group got the same fate when they tried the same in October.17

Kim Il-sung and the right line of the Worker’s Party of Korea had wiped out the red line’s leadership, with hard repression and reactionary violence. It became clear that the threat to the revolution and party was not the left line, but the representatives for the right line. The people who hold the power in the ‘’Democratic People’s Republic of Korea’’ to this day.

As a result of the scandal, the relations between the Communist Party of China and the Worker’s Party of Korea got worse. If it was not yet clear for the international communist movement, time is only going to confirm which side the leadership of the Worker’s Party of Korea stood on.

The Aftermath

In 1966 the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution was initiated in China, and it sent shockwaves across the world. The red line in the international communist movement spread like a wildfire. Everywhere the revisionists and bureaucrats shivered in fear. The Korean leadership was no exception. In a conversation with a Soviet ambassador in 1966, Kim Il-sung said:

[…]the ‘Great Cultural Revolution,’ which might exert a great influence on our Party18

And in November the same year:

“The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution has seriously alarmed us.”19

In fear that the wave of rebellion would reach Korea, and that they would have their own cultural revolution to deal with the Korean leadership, initiated measures to further strengthen its power in the state and party.20

If the Korean leadership was not revisionist and capitalist-roaders, if the Korean state was not filled with bureaucrats, or if there had been a left opposition grassroots in the party – then Kim Il-sung and the right line would not have anything to fear.

In light of the party leaderships reaction against the cultural revolution, there is no surprise that they welcomed the counter-revolution in China with open arms. When the capitalist roaders lead by Deng Xiaoping seized power, the relationship between the ‘’Worker’s Party of Korea’’ and the ‘’Chinese Communist Party’’ improved for the first time in twenty years.

1. International Journal of Korean History (Vol.17 No.2, Aug.2012), “The August Incident” and the Destiny of the Yanan Faction*, page 6.

2. A misunderstood friendship : Mao Zedong, Kim Il-Sung, and Sino-North Korean relations, 1949-1976

3. Letter from Seo Hwi, Yun Gong-heum, Li Pil-gyu, and Kim Gwan to the Chinese Communist Party Central Committee, page 7.

4. International Journal of Korean History (Vol.17 No.2, Aug.2012), “The August Incident” and the Destiny of the Yanan Faction*, page 10.

5. Ibid, page 10.

6. Letter from Seo Hwi, Yun Gong-heum, Li Pil-gyu, and Kim Gwan to the Chinese Communist Party Central Committee, page 10.

7. Ibid, page 11.

8. Ibid, page 11.

9. Draft of a Statement by Yun Gong-heum at the CC Plenum of the Korean Workers’ Party in August 1956, page 2.

10. International Journal of Korean History (Vol.17 No.2, Aug.2012), “The August Incident” and the

11. Memorandum of Conversation with Choe Chang-ik, page 2.

12. International Journal of Korean History (Vol.17 No.2, Aug.2012), “The August Incident” and the Destiny of the Yanan Faction*, page 18.

13. Letter from Seo Hwi, Yun Gong-heum, Li Pil-gyu, and Kim Gwan to the Chinese Communist Party Central Committee, page 12.

14. Ibid, page 12.

15. International Journal of Korean History (Vol.17 No.2, Aug.2012), “The August Incident” and the Destiny of the Yanan Faction*, page 14.

16. Inside North Korea’s Theocracy: The Rise and Sudden Fall of Jang Song-thaek, page 33.

17. International Journal of Korean History (Vol.17 No.2, Aug.2012), “The August Incident” and the Destiny of the Yanan Faction*, page 15.

18. The DPRK Attitude Toward the So-called ‘Cultural Revolution’ in China, page 3.

19. Ibid, page 2.

20. Ibid, page 2

This is taken from: https://tjen-folket.no/index.php/en/2020/05/14/the-august-incident-the-fight-against-the-right-opportunist-line-in-the-workers-party-of-korea/

Tjen Folket Media is a pro-Gonzalo site, so naturally they would be anti-DPRK. But this is an interesting article that I want to preserve.